?? English ?? Deutsch ?? Français ?? Italiano

The eighteenth-century Grand Tourist, at least before the young William Beckford (1760-1844) published his account of his tour on the continent from 1780 to 1781, Dreams, Waking Thoughts, Incidents (1783), typically sought to collect encounters with the celebrated in Paris and Geneva (think of James Boswell’s visits to Rousseau and Voltaire in 1764) and with the aristocrats of Paris and the courtesans of Venice. His subsequent encounter with the antiquities of Rome tended primarily towards the education of his gentlemanly taste on the one hand (think of Goethe’s account of his travels in Italienische Reise) and the adornment of his neo-classical country estate back home (think here of the collection made by Charles Townley from 1765 onwards). His take on sublime landscapes was largely that they were unprofitable and thoroughly uncomfortable (think of the account given by Thomas Gray of crossing the Alps with Horace Walpole in November of 1739, and the fate of Gray’s unfortunate spaniel, Troy, devoured by wolves).

The Romantic tourist was a rather different proposition. Romantic tourism to mainland Europe — in Britain at least — is bracketed by William Wordsworth’s walking-tour in France at the height of the Terror in 1793 and Samuel Rogers’ abortive bid to reach Italy in 1814, when it was thought that Napoleon was safely defeated. In the interim, the leisured learned to tour Britain in search of what we would now call Romantic experiences: achieving appropriate views of ‘sublime’ landscapes, preferably accessorised with historical ruins and associations, or seeking out places with imaginative dimensions conferred upon them by books. Such tourists would in due course export these habits to their travels in post-Napoleonic continental Europe.

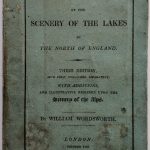

This collection is designed to illustrate some aspects of Romantic tourism. It falls into three unequal sections: the first sketches the variation of tourist experience available within Britain: the sublimities of Fingal’s Cave (exhibit 1), the romance of ‘Ossian’s Hall’ (exhibit 2), the ruins of Tintern Abbey by moonlight (exhibit 3), and the pleasures of mountain ascent detailed in Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes (1822) (exhibit 4). The second selects some symptomatic Romantic tourist experiences available on the continent: identification with Rousseau’s exile on the Ile St Pierre (exhibit 5), melancholy musings at ‘Narcissa’s Tomb’ (exhibit 6), and the sublime horrors of Vesuvius (exhibit 7). The third picks up on Romantic writers as European tourists: considering Byron’s supposed autograph at the Castle of Chillon (exhibit 8), and the travelling box of the Hungarian writer Janos Erdélyi (exhibit 9). Taken together, these examples illustrate the emergence of a new European tourist itinerary, characterised by new Romantic sensibilities and priorities.

See also:

Individual posts: Wordsworth’s Wishing Gate, Le Temple de la Nature

Collection: Romantic Landscapes